Education is one of the most powerful transformative forces in an individual’s life journey. A child’s future role, the opportunities they encounter, and the paths they traverse are often determined by the foundations laid in the classroom. However, in today’s Türkiye, the concept of “equality of opportunity in education” raises a collective question mark in the minds of educators, parents, and students alike. It is a profound question echoing in classrooms, corridors, and homes: “We take the same exam, but we do not have the same means… Is this truly fair?”

This blog post aims to delve into the depths of this fundamental question. We will examine the widening chasm between public and private schools and discuss the impact of this disparity on children’s psychology and academic development. We will analyze how our measurement and evaluation system compresses children into a single standard and the long-term societal consequences of this structure. Furthermore, drawing on successful global examples, we will offer a viable perspective on how a fairer structure can be established for Türkiye.

From Equality to Equity: What is the Real Problem?

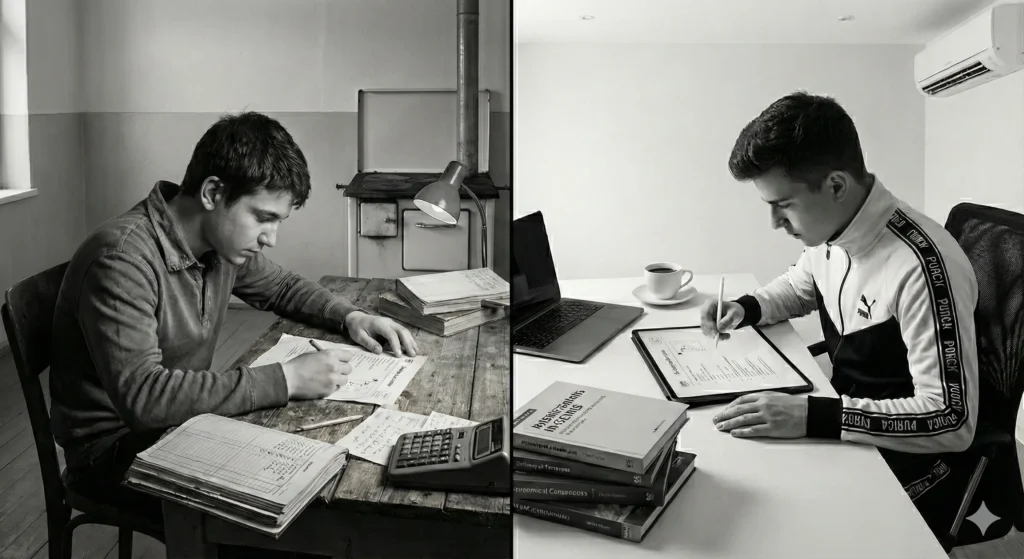

Although the Turkish education system appears historically built on the principle of equality, in practice, it often creates a ground where inequalities are reproduced. Equality implies offering the same opportunities to everyone; however, “the same opportunities” carry different meanings for every child. The difference between a student starting the day without breakfast and another stepping off the school bus directly into a STEM laboratory is not merely a simple contrast (OECD, 2023). A child forced to study at the same table with three siblings paints a similar picture when compared to a peer with a quiet, dedicated study room. Moreover, the fact that math teachers frequently change in one school while another retains a stable faculty for years challenges the perception of equality. In this context, the superficial equality of offered opportunities can mask deep-seated inequalities.

Modern educational science, therefore, focuses on the concept of “equity” rather than “equality.” Equity foresees providing support according to individual needs rather than offering the same facilities to every child (Rawls, 1971). What Türkiye’s education system needs most today is to bring this very principle of equity to life.

The Public vs. Private School Divide: Same Country, Different Realities

A significant portion of public schools in Türkiye function as institutions sustained by the altruistic efforts of teachers, yet often burdened with limited physical facilities and high academic loads. Conversely, private schools increasingly offer various “advantage packages.” These packages include well-equipped laboratories, coding classes, foreign language conversation clubs, art and sports academies, comprehensive counseling units, and even exam coaching and mentorship systems. This totality of resources directly influences students’ performance in centralized exams.

Research by the OECD (2023) indicates that the resources a school offers and a student’s socioeconomic status are as determinative of academic success as teacher quality. In this scenario, the additional support provided to a private school student accumulates opportunities that a child in a public school can never access, and on exam day, it is essentially students from two different worlds who face one another.

Same Exam, Different Worlds: The Justice Problem in Assessment

Centralized exams like LGS and YKS form the backbone of the Turkish education system. However, the underlying assumption of these exams is that “all students have had equal learning opportunities.” This assumption is, unfortunately, far from reality.

While a public school (primary) student may receive two hours of English instruction per week, a private school student might receive ten hours; one may never use a laboratory while the other conducts regular experiments; one tries to cope with exam anxiety without guidance, while the other receives professional psychological support… all these factors fundamentally shake the justice of measurement. From a psychometric perspective, singular exams administered in an environment of unequal opportunity measure the disparity in means rather than the student’s true knowledge and ability. One of the fundamental principles of measurement science is that factors outside a student’s knowledge and skill should not affect test results. Yet, in Türkiye, this is exactly what occurs.

Psychological Repercussions of Inequality

Children in public schools become aware of this inequality at a very young age. They express this with phrases like, “They have it at their school, but we don’t,” or “I am not bad, I just have fewer means.” This awareness can negatively affect children’s self-efficacy, self-esteem, and future expectations. Researchers such as Bandura (1997) and Wigfield & Eccles (2000) have demonstrated that socioeconomic disadvantage reduces academic motivation in the long run.

On the other hand, private school students grow up under a different kind of pressure: the pressure of high expectations, the fear of future failure, and constant performance monitoring. This shows that the psychological effects of inequality surround not only the disadvantaged students but also those who appear advantaged.

The elements determining equality of opportunity in education extend far beyond school walls. Research shows that the neighborhood a child lives in significantly affects school success (Chetty et al., 2016). Factors such as income level, access to libraries and cultural centers, safety when returning home in the evening, and parental education levels shape the out-of-school learning environment. Additionally, the digital divide is striking; while private schools establish advanced STEM laboratories, even basic internet access can be a luxury in some public schools.

Another critical deficiency lies in guidance and career support. While counseling services in most public schools remain limited due to staffing shortages, private schools offer multi-layered support such as individual coaching, career direction, and psychological counseling. This creates an unjust tableau where students run the race of life on different tracks—one struggling through mud, the other sprinting on a tartan track.

When we look at the world, we encounter successful examples showing that fairer education is possible. For instance, Finland has minimized the quality gap between schools nationwide, almost eliminating the disparity between the best and worst schools (Sahlberg, 2011). Similarly, Canada mandates individualized support plans for every student based on the principle that “those in need receive more support” (OECD, 2023). South Korea attempts to close opportunity gaps by expanding extracurricular support programs through extraordinary investments in public schools. The common thread in these examples is the strengthening of public schools and the support of the system’s weakest link.

According to John Rawls’s theory of justice, the justice of a society is measured by the support provided to its weakest member (Rawls, 1971). The fundamental problem in Turkish education is not actually an issue of equality, but a profound lack of equity. No exam, test, or measurement tool can fairly compare children whose starting lines are not equal.

The steps to change this picture must cover a wide spectrum, from short-term remedies to long-term structural reforms. In the first stage, it is an urgent necessity to expand free study and mentorship programs in public schools, establish digital learning centers to increase technology access, and ensure the stability of teaching staff. In the medium term, by developing neighborhood-based disadvantage scoring systems, positive discrimination budgets should be provided to schools in disadvantaged areas, and the social, artistic, and athletic infrastructure of public schools must be strengthened. Our long-term vision should be to implement individualized learning plans, as seen in successful countries like Finland, and to make a gradual transition from a centralized exam-focused system to a more inclusive evaluation model. Naturally, more innovative solutions should be developed through diverse perspectives, and you are welcome to add your suggestions in the comments.

Naturally, this transformation can only be realized not just through ministry policies, but through the collective effort of actors in the field. Teachers can narrow the gap within the classroom through empowering communication and differentiated instruction techniques. Parents can lighten their children’s emotional load by creating a supportive environment at home and maintaining regular contact with the school. Schools, rather than closing in on themselves, should encourage resource sharing by collaborating with universities and other institutions, building a culture that instills psychological resilience in students.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a fairer future is possible. Equality of opportunity in education is more than a pedagogical ideal; it is a reflection of a society’s sense of justice, ethical stance, and vision for the future. Although the gap between public and private schools in Türkiye is growing today, it is not unbridgeable. A child’s destiny should not be drawn by their family’s income, the neighborhood they live in, or the facilities of the school they attend. Every child deserves the right to a fair start to fully realize their potential. Ensuring this right is our collective responsibility.

References

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman.

- Chetty, R., Hendren, N., & Katz, L. F. (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the Moving to Opportunity experiment. American Economic Review, 106(4), 855–902. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150572

- (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/53f23881-en

- Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Sahlberg, P. (2011). Finnish lessons: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland?. Teachers College Press.

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015

Discover more from Serkan Akbulut, PhD(c)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.